Main Themes

- The world is complex (a butterfly flaps its wings and small change in initial conditions leads to disproportionate outputs). So our ability to forecast is existentially limited.

- But some people are demonstrably better forecasters and it’s not just luck. They are consistent.

- Those people are not aliens or geniuses. But they have a mix of qualities and procedures that enable them to forecast at a high level.

- The key to getting better, same as in sports, is useful feedback and iteration. It takes hard work, “deliberate practice” and a commitment to get better.

- Getting better is necessarily a conscious, painstaking process because our natural biases conspire against our judgement in areas where causality is opaque. Which are most questions of interest.

- How groups can hinder or improve forecasting. The role of diversity in group decision making.

- In many contexts, making accurate predictions is actually undesirable. Regrettably, I want to shout Moloch everywhere I look. The expression to look for in the notes: "kto, kogo?" Parts of chapter 12 are so disheartening.

- The leader’s dilemma: decisiveness in the face of uncertainty and intellectual humility

- Objections, progress, and goals in the endeavor of forecasting

Chapter 1: Optimistic Skeptic

- “Skeptic optimist”

- Skeptic because of natural limits to prediction esp as we go further in time because of complexity (aka “chaos theory”). Exemplified by weather forecasting

- Optimist because we can get better by measuring our performance and making adjustments. Measurement is the key prerequisite to improvement.

Chapter 2: Illusions of Knowledge

- An interesting chapter about how unscientific physicians were as recently as post-WWII!

- System 1 speed comes at a cost: “insensitivity to the quality of the evidence on which the judgment is based” “Scientific caution runs against the grain of human nature…to grab on to the first plausible explanation and happily gather supportive evidence without checking its reliability.” (confirmation bias). Science is a methodical way to use doubt to test hypotheses. Doubt is healthy. [Kris: The brain desires order without loose ends. Confidence tells us more about how coherent an explanation is than it tells us about how rigorous attempts to refute it have been.]

- Intuition is pattern recognition not ESP “Whether intuition generates delusion or insight depends on whether you work in a world full of valid cues you can unconsciously register for future use” (ie chess master or firefighters)

Good practice is to trust intuitions but double-check.

Chapter 3: Keeping Score

- To measure forecast accuracy we need to pin down the definition of an outcome and a timeline.

Forecasts often rely on implicit understandings of key terms rather than explicit definitions like ”significant market share” in Steve Ballmer’s forecast. This sort of verbiage is common and it renders forecasts untestable.

- These problems are small versus the problem of probability.

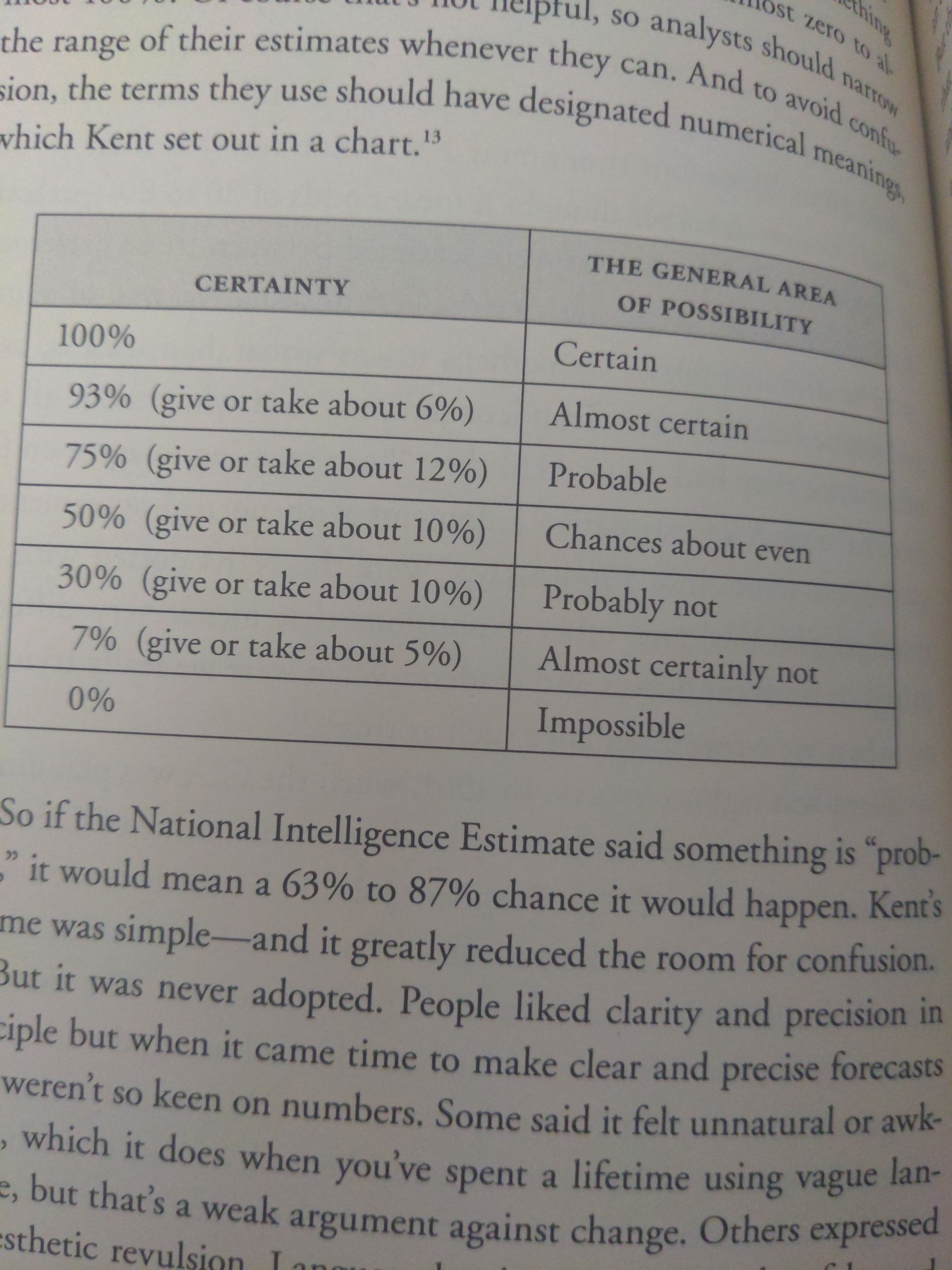

- If say there is a 60% chance of nuclear war there's no way to know if that's accurate without simulating history a thousand times. Mapping probability to language seemed important after massive confusion around the idea the Kennedy was advised that an invasion of Cuba had a “fair chance” of succeeding when the intelligence agency put it at 25%! Sherman Kent proposed this chart but it didn't gain traction

- The downside of using numbers is false precision. (which is why we need confidence intervals)

- And we still have the problem of if a prediction market says the odds of X are 70% and it doesn't happen then people say the wisdom of crowds is wrong (Tetlock calls this the “wrong side of maybe problem”).

- All of this incentivizes elastic language that can be retroactively fit to make a prediction sound more correct. [Kris:Also reminds me of the asymmetry in weather forecasting…forecasters are extra conservative or biased]

- Scoring forecasters We can't rerun history but we can see how forecasters are calibrated over many predictions. The problem is this doesn't work for rare events and with common events, we need patience to get a sufficient sample. Brier Scores are not normalized for volatility so you can't compare them across contexts (it's easier to predict the weather in AZ than in MO)

- How The Wisdom of Crowds Works

- Bits of useful and useless information are distributed throughout a crowd. The useful information all points to a reasonably accurate consensus while the useless information sometimes overshoots and sometime undershoots but critically…cancels out.

- Aggregation works best when the people making judgments have a lot of knowledge about many things.

- Aggregations of aggregations or “polls of polls” can also yield impressive results. That's how foxes think. They pull together information from diverse sources. The metaphor Tetlock uses is they see with a multi-faceted dragonfly's eye. [He gives the example of the guess the number that is 2/3 of the average guess of a number between 0 and 100…if you do the hyper-rational Vulcan Spock method you would get to 0 bc of constant 2/3x math, but if you assume people are lazy you might guess the avg guess is 2/3 of 50 or 33. If you equal weight the lazy answer and the vulcan answer you get 16.5 which is close to the actual result of the experiment which was 13 (bc the avg guess was 19!)]

Chapter 4: Superforecaster

- The Good Judgement Project was funded by US Intelligence apparatus.

- It identified superforecasters that had significantly better forecast Brier scores than chance.

- In addition, the best performers were not lucky, but consistent. In fact, they improved over the years as they collaborated with other superforecasters. A word about luck: If you start with a thousands of forecasters or coin flip predictors then by chance there will always be a few that look highly skilled. The question of whether it’s skill or luck can be examined by noting regression to the mean. The more luck explains the outcome the faster mean reversion occurs. You would not bet on someone who performed well on coin flip predictions to maintain that accuracy. Likewise, in skill endeavors you would not expect regression to the mean to be fast. You don’t expect Steph Curry’s free throw percentage to regress to the NBA average or for Usain Bolt’s track times to converge to the average of the field. The outcome of these tasks is determined mostly by luck. The superforecasters looked like the athletes. The best ones were consistently at the top every year.

Chapter 5: Supersmart?

- About forecasters

- Regular forecasters in the project were in the top 70% of the population in intelligence while superforecasters were in the top 80%. Even the superforecasters are not geniuses.

- Psychological and personality attributes: Yet, these are ordinary people. To them it is fun. “Need for cognition” is the psychological term for the tendency to engage in and enjoy hard mental slogs. [like people who like puzzles] From a personality point of view these are people who score high on “openness”

Still the ability to forecast doesn’t not flow from fixed traits…

- The key ingredient for becoming better at forecasting was not horsepower but how you used it.

Superforecasters pursue point-counterpoint discussions routinely, and they keep them long past the point where most people would succumb to headaches…Forget the old advice to think twice. Superforecasters think thrice and sometimes they are just warming up to do a deeper-dive. For superforecasters hypotheses are to be tested not treasures to be guarded.

- Becoming a better forecaster means knowing the techniques and practicing them.

Techniques:

Fermi estimate

Become comfortable with breaking down hard questions into a series of easier steps that are easy to estimate. Classic example is “how many piano tuners in Chicago?” This can be broken down into questions upon which the answer will depend:

- How many pianos are in Chicago?

- How often is a piano tuned?

- How long does it take to tune a piano?

- How many total piano-tuning hours are there?

- How many full-time jobs does that represent?

Although the answer to each of these questions is a guess, it’s a value that you have a reasonable chance of say making a 90% confidence interval on

Answer the question, not a bait-and-switch version of the question.

When Yassar Arafat died people speculated that he was poisoned by Israelis. But the question posed to superforecasters was whether the Swiss or Italian authorities would find evidence of poisoning.

Answering such a question means considering all the possibilities. And in fact, to be technical, if Arafat was poisoned with polonium which has a short half-life, there’s the possibility he was poisoned but the evidence had decayed by the time his body was exhumed. The superforecasters are very methodical in their thinking, careful not to substitute a the posed question with a more emotionally available question like “did the Israelis poison Arafat?” which is a harder question.

Start with outside view which incorporates base rates because it's a better “anchor”.

This technique harnesses our tendency to anchor by giving a sound basis for our prior.

Once you have a reasonable prior, it’s time to adjust it with an “inside view”. This is focused detective work.

To do this, you do not simply go down a rabbit hole of everything about say Israeli-Palestinian conflict. You form a testable hypothesis about the ways in which the original question could be true.

Hypothesis: Israel poisoned Arafat.

Required conditions:

1. Israel had access to polonium

2. Israel had sufficient incentive to kill Arafat net of the risks

3. Israel had the opportunity to poison Arafat with polonium

Share your thinking with others!

This harnesses the wisdom of crowds.

There are ways to simulate this:

- Tell someone there estimate is wrong and watch them create another one. Then you have 2 estimates to average!

- Ask the person to make the estimate several weeks later. These simulations are known as “the crowd within” in a nod to “wisdom of crowds”.

Chapter 6: Superquants?

- Superforecasters are highly numerate often possessing extensive training in quantitative fields. However, they are not using complicated math. They are nuanced thinkers because their thinking is finely nuanced when it comes to probabilities.

- The extent of most people’s probabilistic thinking is a simple 3 setting dial: yes, no, maybe

- The superforecasters however really demonstrate their skill by being able to discern small differences in percentages. Such as 65% vs 70% or even finer. In fact, when we bucket forecasters by wider probability bands the superforecasters’ advantage over regular forecasters narrows. [Kris: This makes sense to me…traders understand that the difference between 1% and 2% is the difference between 99 to 1 odds and 49 to 1 odds. In payoff space, a small difference in percent is significant so operating in concrete bets forces you to press your thinking to higher resolution. If you are watching a football game from the nosebleeds you can tell what’s happening, but if you want to see who’s limping you need binoculars. So if your environment rewards accuracy and discerning small differences in probability then you become better at discernment. This is very much in keeping with the book’s theme — becoming a better forecaster requires practice which provides feedback. That iterative flow calibrates you.]

- Superforecasters score very low on tests that reveal how much a person believes in fate or the idea that things happen for a reason. It is common to cope with life’s randomness by retrofitting redeeming stories to bad outcomes. Or to minimize the role of luck in our good fortunes. Superforecasters are far less likely to do this. Superforecasters are less interested in “why” (Tetlock highlights Vonnegut’s writing which underlines the futility of asking “why”). They are concerned with how. Psychology shows us that “finding meaning in events is positively correlated with well-being but negatively correlated with foresight. That sets up a depressing possibility: Is misery the price of accuracy?” [Kris: The question is outside the scope of the book but the notion of depressive realism is a thing. Consider this from Morgan Housel’s The Reasonable Optimist: The opposite of excessive dopamine leading to overconfident beliefs could be something called depressive realism. It’s the observation, well documented, that people who are a little depressed have a more accurate view of the world – particularly their ability to accurately predict whether their actions control an outcome. The reasonable optimist is a little pessimistic, a little cynical, maybe even a little glum – not because they’re helpless, but because they’re realistic about how complex the world is, how fickle and opaque people can be, and how history is one long story of surprise, bewilderment, setback, disappointment, confusion, disaster, and humbling reversion to the mean.]

Chapter 7: Supernewsjunkies?

- Strong forecasting depends on starting with reasonable initial guesses…

Superforecasters do monitor the news carefully and factor it into their forecasts, which is bound to give them a big advantage over the less attentive. If that's the decisive factor, then superforecasters' success would tell us nothing more than "it helps to pay attention and keep your forecast up to date"--which is about as enlightening as being told that when polls show a candidate surging into a comfortable lead he is more likely to win. But that's not the whole story. For one thing, superforecasters' initial forecasts were at least 50% more accurate than those of lar forecasters. Even if the tournament had asked for only one forecast, and did not permit updating, superforecasters would have won decisively.

…and effective updating:

More important, it is a huge mistake to belittle belief updating. It is not about mindlessly adjusting forecasts in response to whatever is on CNN. Good updating requires the same skills used in making the initial forecast and is often just as demanding.

- Failure modes:

- Underreaction

This occurs when a forecast clings to a strong prior (”belief perseverance”). This is common when the forecaster’s ego, livelihood, or identity is aligned with their forecast.

- Overreaction The forecast updates out of proportion with the new evidence. This can occur for the opposite reason as underreaction: the forecaster has too little commitment to the prior.

- Avoiding the perils of over/underreaction

Superforecasters have a strong (if not mathematical) intuition for Bayesian updating which depends requires a forecaster’s new belief to depend on the prior belief multiplied by the “diagnostic value” of the new information.

In other words, we need to weigh the new information by our confidence that it matters!

Interpreting a market maker's width as an expression of confidence and using that to update your fair value by weighting their mid-price by the confidence.

If I'm 54.10-54.30 and you are 53.50-53.90 then I'm 2x as confident. So my new fair value is 2/3 x 54.2 +1/3 x 53.70 = 54.03

You must update in proportion to the weight of the new evidence.]

- A final warning

If you start with a sound prior anchored that balances the base rate of the outside view and adjusted for the specifics of the particular situation (the inside view) then most of the time your updates should be incremental. They should only be updated by small percentages.

…But there are cases where a large update is required, so frustratingly, the rule isn’t steadfast. There are exceptions. Sorry.

Chapter 8: Perpetual Beta

- Superforecasters have “growth mindsets”. They believe they can become better with practice. People who exhibit “fixed mindsets” are not interested in techniques for getting better, only in the outcomes.

- Forecasting requires practice to build tacit knowledge. You cannot learn to forecast by reading about it just as you can’t learn to ride a bike by reading about it.

- The role of feedback

- Study of horse handicappers found that the accuracy of their predictions did not improve from the original 5 variables they selected from a large menu of data. As they were given more variables there confidence went up (confirmation bias effect) although their accuracy did not!

- In addition, the handicappers with only 5 variables were well-calibrated. They were close to 2x better than chance at predicting winner 20% vs 10% and they estimated their confidence as such. When they were given more variables their accuracy remained 20% but confidence grew to 30%!]

The practice must be informed practice with timely feedback. If the feedback is not timely, then practice may counterproductive by luring you into a false sense of confidence. Police fancy themselves good at lie detection, but they actually receive feedback on significant lags (for example, when the accused go to trial).

So frequent practice with delayed feedback raises their confidence more than their accuracy leaving them poorly calibrated!

[Kris: Reminds me of the Paul Slovic horse bettor study: Irrelevant data increases your confidence without increasing your accuracy

- Transferrence

To get better at a certain type of forecasting you must practice that specific type. While bridge players and meteorologists became great forecasters via feedback, there is no transference of skills across domains.

- Why is accurate feedback so difficult?

- Hindsight bias: knowing the outcome distorts our memory of what we expected (great example was how everyone forgets that GW Bush was a heavy favorite to win a second term because of his popularity after the Gulf War)

- Vague language of forecasts makes measurement difficult. Like astrology, vague wording is elastic, stretched to fit over one’s self-image.

[Kris: This chapter pairs well with my discussion of how what makes a professional is the desire to improve and doing rigorous post-mortems to learn from mistakes. See Being A Pro And Permission To Be Serious]

Chapter 9: Superteams

The consensus cause of the Bay of Pigs fiasco was groupthink:

"members of any small cohesive group tend to maintain esprit de corps by unconsciously developing a number of shared illusions and related norms that interfere with critical thinking and reality testing."

Groups that get along too well don't question assumptions or confront uncomfortable facts. So everyone agrees, which is pleasant, and the fact that everyone agrees is tacitly taken to be proof the group is on the right track.

Yet, the same advisors to Kennedy who botched the Bay of Pigs, effectively considered 10 different plans to avert the Cuban Missle Crisis.

- So what makes teams harness the wisdom of crowds or succumb to the madness of crowds? The key is whether the members of the group can maintain independent thought while still benefitting from the aggregation. We want the member’s mistakes to be independent and uncorrelated!

- How to foster healthy teams and contention

- suspend hierarchy

- consult outsiders

- withhold the leader’s view so discourse can be more honest (avoid “CEO disease”)

- “psychological safety”: culture of mutual respect so people can challenge each other or admit ignorance [Kris: SIG’s Todd Simkin emphasizes the importance of this in decision-making]

- “diversity trumps ability”: the provocative claim that highlights how the aggregation of different perspectives can improve judgment. The key to diversity is cognitive diversity.

- When they constructed the superteams they optimized for ability and those teams happened to be highly diverse because the superforecasters themselves were highly diverse.

- The extremizing algorithm is a technique to make say a 70% prediction closer to the extreme, perhaps bumping it to 85%. It’s a technique that is employed when the forecasters have diverse perspectives. You would want to do the opposite to combat groupthink (haircut the prediction probability) if the teams is comprised of people who think the same or possess similar knowledge. (This algo allowed teams of regular forecasters to actually perform better than some superteams).

- [Kris: Note that in data analysis, this is the same logic by which correlated observations “shrink” the sample size!]

- The verdict: teams are more effective Individuals are no match for healthy teams and in fact teams of superforecasters were able to outperform prediction markets

The results were clear-cut each year. Teams of ordinary forecasters beat the wisdom of the crowd by about 10%. Prediction markets beat ordinary teams by about 20%. And superteams beat prediction markets by 15% to 30%.

- Emergence

- Teams are more than the sum of their parts. Groupthink can emerge from individuals who are actively open-minded.

Chapter 10: The Leader’s Dilemma

Leaders are called on to be confident, decisive, and deliver a vision. These qualities seem to be at odds with superforecasters who are never certain of anything, humble, and intellectually agnostic.

Reconciling this dilemma comes from studying the Prussian military of the late 1800s. With a appreciation for nothing being certain as well as the pressure to take fast , decisive action within that uncertainty gave rise to “mission command”.

- Mission Command

- The balance was to have a central bird’s eye view command dictate the strategic objectives, but decentralize how to do it. Push the decisions down the hierarchy to the boots on the ground.

- Much of the chapter is a discussion of various military leaders who embodied and were influenced by the “mission command” philosophy. They needed to strike the right balance between thinking and doing which is often presented as a false dichotomy.

- I enjoyed this section regarding General Petraeus who served in Iraq in the early 2000s:

Petraeus also supports sending officers to top universities for graduate education, not to acquire a body of knowledge, although that is a secondary benefit, but to encounter surprises of another kind. "It teaches you that there are seriously bright people out in the world who have very different basic assumptions about a variety of different topics and therefore arrive at conclusions on issues that are very, very different from one's own and very different from mainstream kind of thinking, particularly in uniform," Petraeus said Like encountering shocks on a battlefield, grappling with another way of thinking trains officers to be mentally flexible. Petraeus speaks from experience. Thirteen years after graduating from West Point he earned a PhD in international relations from Princeton University, an experience he calls "invaluable.”

- Humility

Humility can sometimes conjure timidness or self-doubt. But when we speak of humility it’s intellectual humility. It acknowledges that there’s always more to learn and complexity means that there is plenty we will never know. But we still need to act. It’s possible to be humble about the limits of one’s knowledge while still having the courage and confidence to make critical decisions with resolve.

Chapter 11: Are They Really So Super?

Kahneman wondered if superforecasters are “different kinds of people or people who do different kinds of things?”

- A bit of both

While superforecasters score higher than average on intelligence and open-mindedness they are not outliers.

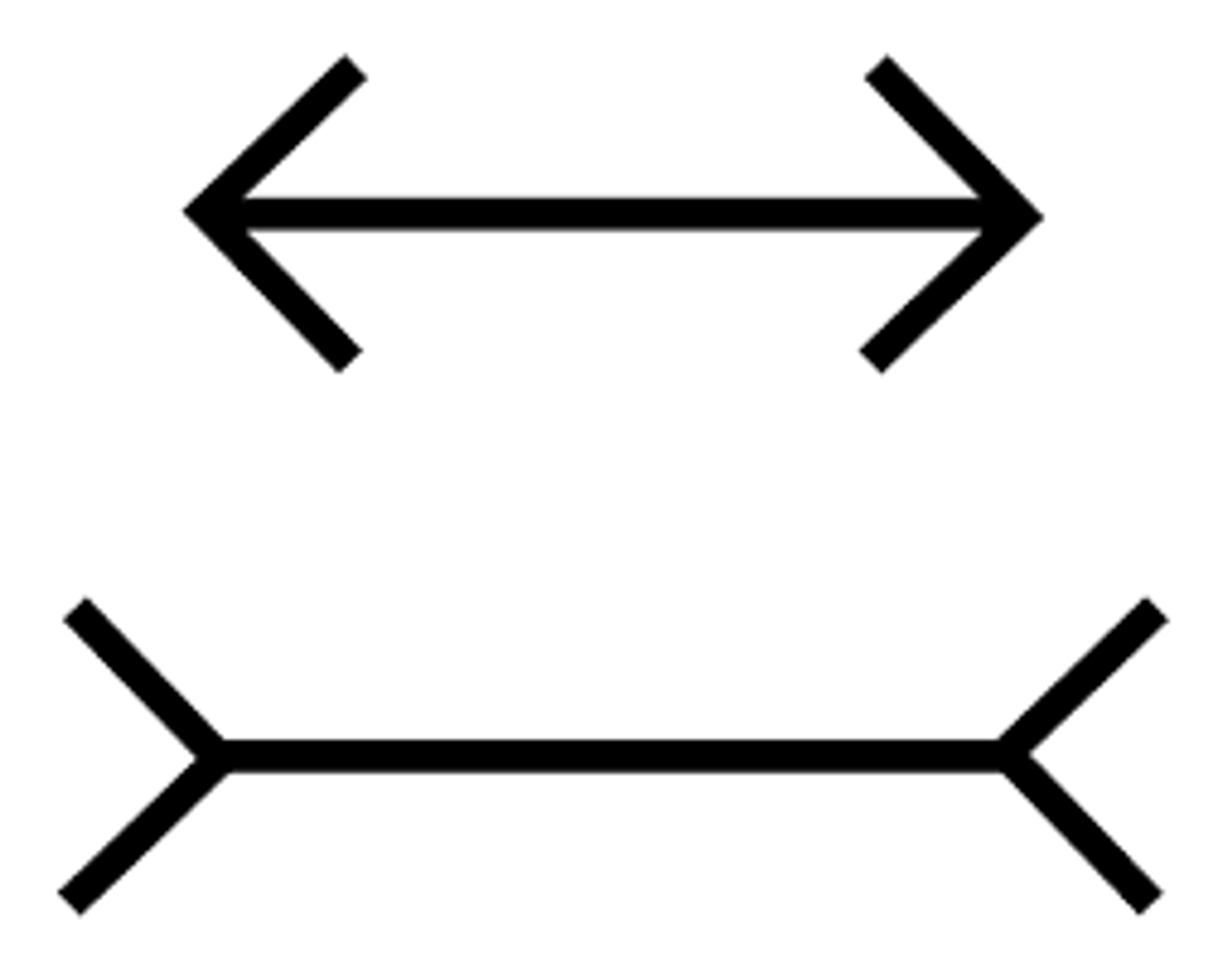

In fact, the biases of our system 1 gut inferences are so fast, and automatic that we fall for them even if we know about them. Like optical illusions. Even if we understand the Muller-Lyer illusion we still cannot agree the lines are equal without measuring!

We can only monitor the answers that bubble up into consciousness — and when we have the time and cognitive capacity, use a ruler to check.

But there’s some optimism, there is evidence that superforecasters are able to effectively make system 2 type adjustments part of their system 1.

For example, Kahneman’s research says people are “scope invariant”…for example if you ask how much money people would spend to solve climate change their answer is roughly the same regardless of the impact (killing 100k trees vs killing 100M trees). This even holds for time horizon…most people would not vary their answer much if you ask them if X will happen in 3 months vs say 12 months.

But superforecasters seem to be automatically inoculated against scope invariance, a product of habitual effort in forecasting, not natural inclination.

- The Black Swan objection

- Many events categorized as black swans are actually grey swans. Unlikely but conceivable. We can make progress with those.

- Everything is a prediction, and as investors already understand, compounding is built upon incremental improvement but leads to wildly different terminal outcomes. If we can improve judgment incrementally it does matter in the big picture.

Nassim Taleb insists that black swans, and black swans alone, determine the course of history. "History and societies do not crawl," he wrote. "They make jumps." The implication for my efforts to improve foresight is devastating: IARPA has commissioned a fool's errand. What matters can't be forecast and what can be forecast doesn't matter. Believing otherwise lulls us into a false sense of security. In this view, I have taken a scientific step backward. In my EPJ research, I got it roughly right with the punch line about experts and the dart-throwing chimp. But my Good Judgment Project is premised on misconceptions, panders to desperation, and fosters foolish complacency.

Rebuttals:

[Kris: I thought this was an important quote dealing with the nihilism that accompanies profound humility and the evidence that we can actually be effective agents:

Savoring how history could have generated an infinite array of alternative outcomes and could now generate a similar array of alternative futures, is like contemplating the one hundred billion known stars in our galaxy and the one hundred billion known galaxies. It instills profound humility.

Kahneman, Taleb, and I agree on that much. But I also believe that humility should not obscure the fact that people can, with considerable effort, make accurate forecasts about at least some developments that really do matter. To be sure, in the big scheme of things, human foresight is puny, but it is nothing to sniff at when you live on that puny human scale.]

Chapter 12: What’s Next?

Reflections on the goals, progress, and obstacles for superforecasting

Obstacles

- A cynical but realistic observation: Not everyone is interested in better predictions.

- Like hardball operators before and since, Vladimir Lenin many insisted politics, defined broadly, was nothing more than a struggle for power, or as he memorably put it, "kto, kogo?" That literally means "who, whom" and it was Lenin's shorthand for "Who does what to whom?" Arguments and evidence are lovely adornments but what matters is the ceaseless contest to be the kto, not the kogo. It follows that the goal of forecasting is not to see what's coming. It is to advance the interests of the forecaster and the forecaster's tribe. Accurate forecasts may help do that sometimes, and when they do accuracy is welcome, but it is pushed aside if that's what the pursuit of power requires.

- Example: Dick Morris-a Republican pollster defended himself after predicting a Romney victory: “Nobody thought there was a chance of victory and I felt that it was my duty at that point to go out and say what I said" Of course, Morris may have lied about having lied, but the fact that Morris felt this defense was plausible says plenty about the kto-kogo world he operates in. [Kris: these points all underscore something I observe: most people are not interested in accuracy. They just talk their own book.]

- The pitfalls of measurement

- Numbers are fine and useful things but… Not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts.' The danger is "Where wisdom once was, quantification will now be." Consider a hospital boasting that 100% of its patients live-without mentioning that the hospital achieves this bragging right by turning away the sickest patients. Numbers must be constantly scrutinized and improved, which can be an unnerving process because it is unending. Progressive improvement is attainable. Perfection is not.

- Can we only answer small questions? A common objection to the narrow questions in the forecasting studies. Some questions feel too big to answer with any intellectual honesty. So we confront a dilemma. What matters is the big question, but the big question can't be scored. The little question doesn't matter but it can be scored, so the IARPA tournament went with it. You could say we were so hell-bent on looking scientific that we counted what doesn't count. Do we really have to choose between posing big and important questions that can't be scored or small and less important questions that can be? The solution is not earth-shattering: question clustering Consider the question of whether we will go to war with North Korea. We can see that the big question is composed of many small questions. One is "Will North Korea test a rocket?" If it does, it will escalate the conflict a little. If it doesn't, it could cool things down a little. That one tiny question doesn't nail down the big question, but it does contribute a little insight. And if we ask many tiny but-pertinent questions, we can close in on an answer for the big question. Will North Korea conduct another nuclear test? Will it rebuff diplomatic talks on its nuclear program? Will it fire artillery at South Korea? Will a North Korean ship fire on a South Korean ship? The answers are cumulative. The more yeses, the likelier the answer to the big question is "This is going to end badly.”

- The importance of asking good questions Foresight is one element of good judgment, but there are others, including some that cannot be counted and run through a scientist's algorithms—moral judgment, for one. Another critical dimension of good judgment is asking good questions. Indeed, a farsighted forecast flagging disaster or opportunity can't happen until someone thinks to pose the question. What qualifies as a good question? It's one that gets us thinking about something worth thinking about. He uses the example of pundit and Middle East expert Tom Friedman (throughout the book Tetlock is skeptical of Friedman’s track record on forecasting mostly because his formulations are vague and too slippery to pin down for scoring) who asks provocative questions. For example, is Saddam the way he is because of how Irag is or is Saddam the reason Iraq is the way it is? While we may assume that a superforecaster would also be a superquestioner, and vice versa, we don't actually know that. Indeed, my best scientific guess is that they often are not. The psychological recipe for the ideal superforecaster may prove to be quite different from that for the ideal superquestioner, as superb question generation often seems to accompany a hedgehog-like incisiveness and confidence that one has a Big Idea grasp of the deep drivers of an event. That's quite a different mindset from the foxy eclecticism and sensitivity to uncertainty that characterizes superb forecasting.

Progress

- Even if the majority uses predictions to reinforce their positions, there are pockets of intellectual honesty

- Medicine made great strides in becoming evidence-based despite the majority of doctors who, already having respect, had more to lose status-wise from scrutiny and accountability. It was a small cadre of doctors whose relentless drive to make the sick well who pushed the field forward.

- Sports provide striking examples of the growth and power of evidence-based thinking. As James Surowiecki noted in the New Yorker, both athletes and teams have improved dramatically over the last thirty or forty years. In part, that's because the stakes are bigger. But it also happened because what they are doing has increasingly become evidence-based. "When John Madden coached the Oakland Raiders, he would force players to practice at midday in August in full pads," Surowiecki noted. "Don Shula, when he was head coach of the Baltimore Colts, insisted that his players practice without access to water." Thanks to scientific research in human performance, such gut-informed techniques are going the way of bloodletting in medicine. Training is "far more rational and data-driven," Surowiecki wrote. So is team development, thanks to rapid advances in "Moneyball"-style analytics. "A key part of the 'performance revolution' in sports, then, is the story of how organizations, in a systematic way, set about making employees more effective and productive.”

Goals

- Cooperation When a debate like "Keynesians versus Austrians" emerges, key figures could work together with the help of trusted third parties—to identify what they disagree about and which forecasts would meaningfully test those disagreements. The key is precision. It's one thing for Austrians to say a policy will cause inflation and Keynesians to say it won't. But how much inflation? Measured by what benchmark? Over what time period? The result must be a forecast question that reduces ambiguity to an absolute minimum. A single dot on a canvas is not a painting and a single bet cannot resolve a complex theoretical dispute. This will take many questions and question clusters. Of course, it's possible that if large numbers of questions are asked, each side may be right on some forecasts but wrong on others and the final outcome won't generate the banner headlines that celebrity bets sometimes do. But as software engineers say, that's a feature, not a bug. A major point of view rarely has zero merit, and if a forecasting contest produces a split decision we will have learned that the reality is more mixed than either side thought. If learning, not gloating, is the goal, that is progress. Each side may want to be right but they should want the truth more. Sadly, in noisy public arenas, strident voices dominate debates, and they have zero interest in adversarial collaboration. But let's not make the cynic's mistake of thinking that those who dominate debates are the only debaters. We hear them most because they are the loudest and the media reward people who shout into bullhorns. But there are less voluble and more reasonable voices. With their adversaries and a moderator, let them design clear tests of their beliefs. When results run against their beliefs, some will try to rationalize away the facts but they will pay a reputational price. Others will do the honorable thing and say, "I was wrong." But most important, we can all watch, see the results, and get a little wiser. All we have to do is get serious about keeping score.

- The way forward takes courage What would help is a sweeping commitment to evaluation: Keep score. Analyze results. Learn what works and what doesn't. That requires numbers, and numbers would leave the [entrenched interests] vulnerable to the wrong-side-of-maybe fallacy (this is the tendency for people to forget that a 70% prediction still has a 30% chance of failure), lacking any cover the next time they blow a big call.

Imagine a director of National Intelligence in a congressional hearing to explain why intelligence analysts didn't see some huge event coming-a revolution or a terrorist strike-before it was too late. "Well, we're generally pretty good at these things and getting better," he says, taking out a chart. "See? Our evaluations show the Brier scores of our analysts are solid and there has been significant improvement over time. We have even caught up with those annoying superforecasters. So while it's true we missed this important event, and terrible consequences followed, it's important to keep these statistics in mind.”

Summary of how to be a better forecaster

[the main point of chapter 3]

It's possible to make better forecasts but it requires real work and a resistance to our default tendency to confirm and needs for narrative coherence. It is a humble endeavor requiring open-mindedness, self-criticism, and learning from feedback. It's not some magical trait like intelligence. It's an overall approach.

[from chapter 7]

Superforecasting isn't a paint-by-numbers method but superforecasters often tackle questions in a roughly similar way—one that any one of us can follow.

- Unpack the question into components.

- Distinguish as sharply as you can between the known and unknown and leave no assumptions unscrutinized.

- Adopt the outside view and put the problem into a comparative perspective that downplays its uniqueness and treats it as a special case of a wider class of phenomena.

- Then adopt the inside view that plays up the uniqueness of the problem. Also explore the similarities and differences between your views and those of others—and pay special attention to prediction markets and other methods of extracting “wisdom from crowds”

- Synthesize all these different views into a single vision

- Finally, express your judgment as precisely as you can, probabilistically using a finely-grained scale of probability.

[End of Chapter 8: Summarizing The Profile of a Superforecaster]

While not every trait is equally important the degree to which one is committed to belief updating and self-improvement is roughly 3x as powerful predictor as its closest rival, intelligence. This mirrors Edison’s idea that the task is 75% perspiration, 25% inspiration.

Philosophic outlook

- CAUTIOUS: Nothing is certain

- HUMBLE: Reality is infinitely complex

- NONDETERMINISTIC: What happens is not meant to be and does not have to happen

Thinking styles

- ACTIVELY OPEN-MINDED: Beliefs are hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be protected

- INTELLIGENT AND KNOWLEDGEABLE, WITH A "NEED FOR COGNITION": Intellectually curious, enjoy puzzles and mental challenges

- REFLECTIVE: Introspective and self-critical

- NUMERATE: Comfortable with numbers

Methods

- PRAGMATIC: Not wedded to any idea or agenda

- ANALYTICAL: Capable of stepping back from the tip-of your-nose perspective and considering other views

- DRAGONFLY-EYED: Value diverse views and synthesize them into their own

- PROBABILISTIC: Judge using many grades of maybe

- THOUGHTFUL UPDATERS: When facts change, they change their minds

- GOOD INTUITIVE PSYCHOLOGISTS: Aware of the value of checking thinking for cognitive and emotional biases

Work ethic

- A GROWTH MINDSET: Believe it's possible to get better

- GRIT: Determined to keep at it however long it takes